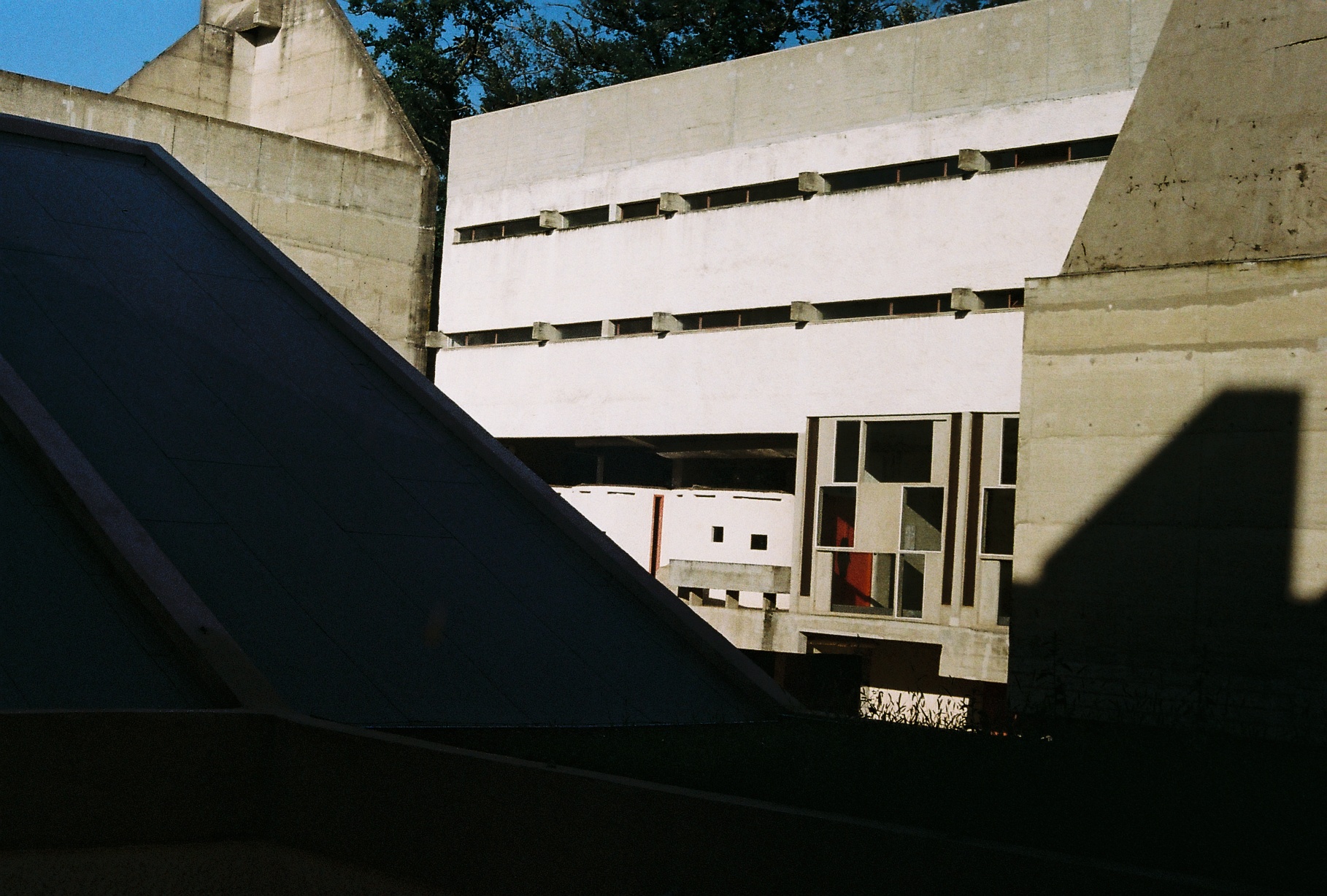

At the beginning of September, I had the opportunity to visit Le Corbusier’s buildings for a few days. We began with the small house he designed for his parents on the shore of Lake Geneva, then stayed for three days in the monastery of La Tourette. The trip ended with visits to La Habitation, the church in Firminy, and the steel residential house La Carte in Geneva.

The journey left me with mixed feelings. Awe, aesthetic fulfillment, and a sense of searching intertwined with an elusive feeling that something was different. I had to critically confront the enthusiasm of my professors with my own thoughts and emotions. A few days later, I gave my intuitive doubts a more concrete form. Below is a collection of thoughts, perhaps chaotic at first glance, but ones that help me shape my own path in architecture, both in my mind and in my heart, accompanied by drawings and photos from the trip.

I realized what felt wrong about Le Corbusier’s buildings.

Houses should belong to the people who inhabit them. That is why it was important for me to take part in the ritual at the church. The first evening was the most beautiful one. I saw the building bathed in wonderful light – and I don’t mean only the natural one (incidentally, I never saw light like that again during the following days). That first day, the post-rain light was soft, and I felt as if it embraced the building. In the days that followed, it seemed to dominate it instead.

I was sorry that the monks had left, even though I completely understood why. 🙂 In the end, I realized that what remained in me was a faint memory of a hotel-like trip, although an exceptional one, of course. I deeply value the experience, yet I confirm to myself that I prefer a more intimate way of discovering architecture, when I have space for quiet perception, without bringing so much of my own life into it. So that I can perceive it objectively.

In the end, I do not think the architecture itself was at fault, rather the situation we placed it in.

Houses should belong to the people who live in them, to living people. Perhaps it sounds like a play on words, but I would rather focus solely on the building itself and not know who designed it. If a solution is right, it does not matter whether it was invented by Corbusier or Xenakis. What matters is that it is done correctly, that is the value that transcends time and can be judged.

In the case of La Tourette, for me the idea that “it should belong to people” means that, similarly to the Faculty of Architecture building by Mrs. Šrámková, there are strict rules for both inner and outer aesthetics. I think that is, in a way, a disadvantage. People tend to like it – it is easier to follow someone else’s rules than to take responsibility for your own. Of course, it is demanding, since we are “creaturely” by nature, but I think a person should have the possibility to improve things, even if the architect intended them as perfectly as possible.

Architecture makes the most sense to me as a backdrop for life, just as nature is a backdrop for living beings. That means the greatest experience for me occurs when something new emerges from the connection between architecture and the human being. And in that moment, we cease to be victims of the past or the future. How different these backdrops can become when filled with the personality of their inhabitants is shown beautifully in the example of two apartments in La Carte. At that moment, housing felt closer to me than the church. It is perhaps the most intimate thing we can share with another person through architecture.

I believe architecture is right when I feel comfortable in it at first, without knowing why, and only afterwards find it interesting. Not the other way around.

In La Tourette, every wall and every window is strictly defined, so much so that one cannot truly touch or change them. Corbusier designed an enormous number of details, all very artistic, but after several days of living in his building I felt that these details overwhelmed the overall harmony. I tend to think this was more due to the situation we placed the building in, and to us – the people who are far from its original, intended function.

“Architecture with a capital A begins only when the project gains the ability to take flight, when it frees itself from its constants, grows wings, and can evolve in other directions.”

Álvaro Siza Vieira